By Angela Dripps, Seasonal Naturalist

If you’ve gone creeking this summer, you’ve probably found some pretty cool critters in your nets and buckets. As a former water quality scientist with the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, I spent 13 summers “creeking” in rivers and streams all over the state collecting thousands of aquatic insects, crustaceans, mollusks, and worms (Yes, it was an awesome job!). In that time, I found my share of cool critters in my own nets and buckets, but no critter has managed to continuously capture my curiosity more than the caddisfly.

Unless you are an entomologist or a fly fisherman, chances are you’ve never heard of caddisflies. Caddisflies are insects of the order Trichoptera, which means “hair wing” and refers to the hairy wings of the terrestrial, moth-like adults. Caddisflies undergo a complete metamorphosis that consists of an egg, larva, pupa, and adult. You’re probably familiar with another group of insects that undergo complete metamorphosis – the Lepidoptera, which are the butterflies and moths. Unlike butterflies and moths, the egg, larva, and pupa stage of the caddisfly all occur underwater. What the caddisfly can do as a larva, however, is what makes them so incredibly cool.

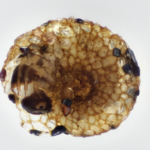

Caddisfly larvae are underwater architects! They can build an underwater retreat or a portable case in which to live, feed, and grow. Using silk glands located on their labium (“lower lip”), many caddisfly larva glue together pebbles, sand grains, twigs, leaf cuttings, grasses, or snail shells into a very specific shape that is unique to their type, while some simply spin a silk net amongst rocks. They live inside the case or retreat as they grow as larva and use it for finding food as well as for protection from predators.

My favorite caddisflies are the ones that build portable cases. When caddisflies emerge from their egg, they immediately begin building a case around their bodies. Once they finish the case, they carry it around with them hermit crab-style. However, unlike hermit crabs that look for a bigger shell when they outgrow the old one, caddisflies simply build a bigger case around the smaller one. The newer, larger cases are increasingly intricate in their design – one species makes a case out of sand grains that looks like a snail shell! When case-building caddisflies are ready to pupate, they simply spin more silk to seal off the entrance, and metamorphosis takes place inside the case. Newly transformed adults emerge from the underwater case, make their way to land, dry off their wings, then begin life as a terrestrial insect.

Caddisflies are important members of freshwater ecosystems and can be found in rivers, streams, wetlands, ponds, and lakes on every continent except Antarctica. They help break down organic matter, filter out particulates, and provide food for fish and other animals. Caddisflies are also sensitive to pollution, so finding caddisflies in your net can indicate good water quality. Caddisflies have also been used to make jewelry (Google “caddisfly jewelry”, you’ll be amazed!) and many scientists have studied their sticky-when-wet silk in hopes of making bandages that will stick to wet wounds. What’s not to love about caddisflies?

So, when you are creeking at Shale Hollow Park or elsewhere, look closely at the haul in your net. If one of your sticks, stones, or leaves starts walking away, you may have just found the coolest critter in the creek – the caddisfly!